Future Man

Originally printed in Surfer’s Journal

Jim Evans

TAKE LAS VIRGENES ROAD FROM THE 101 FREEWAY and drive into the heart of Malibu Canyon past hoary Mulholland and keep going to Piuma Road. Then, take a left and climb through the rolling hills up toward the mountain peaks and find Las Flores Canyon Road, the downward glide of which will take you to the sea-breeze side of the slope and the easy-to-miss cul-de- sac where Jim Evans lives. Getting there is the stuff of “Dead Man’s Curve” nightmares. Kids high on downhill skateboarding daredevilry pass going one way while nin- jas on rice rockets scream by going the other. Overhead, red-tail hawks interrupt an otherwise spotless blue sky. It’s a perfect afternoon for Malibu mythmaking.

Maybe too perfect. The next hairpin summons slowdowns and sirens as EMTs tend to a would-be hero, crashed and burned by the side of the road while his weekend-warrior buddies look on aghast. There’s nothing to do but offer a prayer and climb, baby, climb. This is Southern California, after all, and legends are hard won if at all.

The drive to Evans’ house reminds me of something Jacqueline Miro—the editor, urban planner, and most pertinently, Swell exhibit co-curator—said about Evans himself in a recent conversation. Swell, which had a nice 2010 run at Neyehaus Gallery in Manhattan, was one of the more recent—and better—attempts by the Empire City to come to terms with 60 years of the Exploding California Inevitable, aka surf culture. In putting together the show —which featured Evans, Craig Stecyk, Ed Ruscha, Billy Al Bengston, Sandow Birk, and many more—Miro was drawn to the sense of adventure and expansiveness she found among the Golden State’s art and artists.

“There’s a sense of courage and character-building on the West Coast that I find lacking in New York City,” says Miro. “This runs from Jim Evans to Billy Al Bengston to Ed Moses and it’s something I admire very much.”

As for Evans, on whom we’ll be spending most of our time here, Miro succinctly nails the source of his enduring relevance.

“There’s just so much history I love that Jim’s been a part of.”

For Miro, a Salvadoran who grew up surfing from the age of nine before moving on to headier pursuits such as studying architecture at Tulane, and getting her graduate degrees in Paris, it was an early ’90s Jane’s Addiction piece that led her down the rabbit hole that ended up with Jim Evans in New York as one of Swell’s stars.

“These posters were so powerful in my mind. He became a Gerry Lopez to me, something of that quality,” she explains. “Jim, as an artist, has the ability to capture the zeitgeist of whatever decade he’s portraying. Whether he’s doing surf or grunge or The Hunger Games today, he gets the essence of that time. He really does believe that what surrounds a certain movement is as important as what’s being produced.”

***

POSTWAR SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA is easy to imagine, but harder to grasp.

A new generation of Midwesterners, among them James Leroy Evans—a scrappy kid from Chicago who enlisted at the age of 17 when Pearl Harbor was attacked— arrived for boot camp, got a quick glimpse of sun, surf, and palm trees, was quickly shipped off from Camp Pendleton to Midway, Guadalcanal, and Iwo Jima. When they came back, these kids brought with them the influences of the wider world to which Southern California was the new portal.

As they settled in to raise families, the now-mighty Southern California military industrial complex brought with it a pervasive cultural schizophrenia: a newfound prosperity fraught with an entirely new nuclear anxiety. California was suddenly both the beginning and the beginning of the end. And meanwhile, all the violence of bloody war in the Pacific festered like an infection just beneath the skin.

What’s a postwar generation to do with all that?

A sensible young man, born right around the mid- century mark into the welcoming embrace of Oceanside, California, home to Phil Edwards and L.J. Richards, might go surfing. And play some Buddy Holly, Link Wray, psycho surf music while he was at it. Which is what Jim Evans did.

“It was really easy to crank up the reverb and hit a minor chord and you were there,” laughs Evans. “I thought I was going to be a musician and not an artist.”

We’re sitting on the deck overlooking the front yard of his tastefully modern concrete and steel home. The garden is a drought-resistant ensemble of native plants and rocks. There’s not a lot of fuel onsite for the fires that can consume whole swaths of Malibu at a time. Lessons learned.

The comfortable minimalism carries over to the interiors, which, for a guy whose artwork is known for its vibrant color palette, is subdued in blacks, browns, and grays. Evans’ office, adjacent to the deck, has the look and feel of an elaborate command-control station—with a daunting lineup of consoles, digital hardware, screens and wires. If there’s a Matrix, it can be hacked from here. Evans gracefully lets his visitor pick up and strum the ’62 Fender Jaguar propped against a north-facing wall, one of the visible nods to the age of analog.

As a kid, Evans demonstrated a proclivity for art, and by the time he was close to graduating high school, he had a few seminal moments under his belt. One occurred when he ran across a guy doing hand-brush sign painting at a local business. “I told him I’d work for free if he taught me how to do that,” says Evans, tall and fit in his early 60s, and still wearing mostly black.

An apprenticeship began and Evans started learning brushstroke and script the old-fashioned way. He also learned that art could be both commodity and commerce when a high school teacher agreed to pass him provided Evans paint the sign for his surf shop.

“In the morning, I’d surf and in the afternoon I’d paint his surf shop.”

And in the evening he’d play in the bands for which he did the art, logos, and promotional materials. Before long, other bands were paying Evans to draw out their personas. The relationships between art and identity started to take root in his consciousness.

But many other things were in there, too: the Bikini Atoll hydrogen-bomb detonations, the fallout of which literally poisoned the crew of a Japanese fishing boat and figuratively awakened the sleeping monster, Godzilla; the Korean War; the Cuban Missile Crisis; JFK’s assassination; the first wave of friends coming back from Vietnam who “weren’t the same guys anymore.”

The utopian ideal of waves, of surf, and sun was still lingering in the atmosphere, but so was change, and it was moving fast.

“By ’66, things had changed really, really fundamentally,” says Evans. “The ’60s opened up a floodgate of change that I can’t say has happened before or since.”

There was LSD, of course, and Evans had a common initiation. “Being an idiot, I didn’t feel anything and took another [hit]. It was never the same after that.”

Forays into Eastern Mysticism, the Tibetan Book of the Dead followed. “There was this giant world I knew nothing about.” Evans says his head became like a projector, taking in all that cultural dissonance and putting it down on paper in his drawings and cartoons.

“I thought I might [have been] retarded, or had ruined my brain,” he laughs.

To stave off the draft, Evans enlisted in both the Naval Reserve and the Chouinard Art Institute, now known as CalArts.

“It was just a big free-for-all at that time,” says Evans. “I just cartooned. I was basically a dopey cartoonist.”

But dopey cartooning sometimes seemed like the perfect medium to make sense of the times. And doing comics for underground papers like the L.A. Free Press and then-counterculture mags such as Surfer, connected Evans with seminal ZAP Comix artists like R. Crumb, Manuel “Spain” Rodriguez, Robert Williams and, most importantly, Rick Griffin.

***

EVANS MADE LASTING CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE GENRE, including the Yellow Dog series, which came out of Berkeley’s legendary Print Mint, along with his own Dying Dolphin and, of course, Tales From The Tube, Surfer’s early ’70s gonzo brainchild. Some of the work found him collaborating with Rick Griffin, who was also busy at the time helping to put the Haight-Ashbury ballroom scene on the map.

Meanwhile, Evans was soaking in the Venice Beach vibe. “It was a fertile time for art—late ’60s Venice,” says Evans. “There were a lot of great artists. I was in awe.” When Griffin moved back to Los Angeles, he offloaded assignments to Evans. Before long, Evans was solidly in the mix. “I started getting so much work, I didn’t even bother to finish art school,” he says.

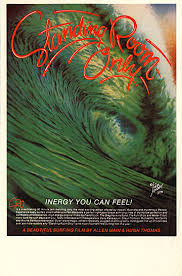

After an extended North Shore surfing safari that saw Evans testing himself at Sunset and Pipeline while creating iconic posters for Hal Jepsen’s A Sea For Yourself, Bud Browne’s Going Surfin’ series, and the instant Aussie classics On Any Morning and A Winter’s Tale, Evans returned to the mainland in 1973.

Back home, he continued to trade in the most persuasive cultural currency of the day, doing album and logo work for the likes of Jan and Dean, The Beach Boys, Robbie Krieger, and Chicago.

Jim Evans

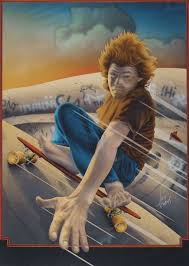

Though the logos he designed for the Beach Boys and Chicago are still in use, arguably the biggest impact Evans made was with the Cadillac Wheels campaign, which both ignited and encapsulated the mid-’70s polyurethane- fueled skateboard revolution.

The campaigns were broad concepts, painted with a stunning attention to detail, contrast, movement, and authenticity, all meant to communicate a paradigm shift. Evans cranked out one a month for five months, working

with airbrush and dye, pencil for detail, and toothbrush for texture.

For Evans it seemed like the creative universe was ever-expanding. “I felt really conscious of it,” he says. “I thought it would move linearly.”

Unfortunately, things slowed down right after the skate and punk explosion.

“The combination of Reagan and AIDS did a lot to bring things to a halt,” says Evans. “I didn’t know there were that many pissed off people.”

Evans devoted his energies to doing what a lot of people tried to do in the ’80s—make money. “There was a point when I started to separate from Rick and those guys, and that was when I decided to feed my family,” he says.

The ’80s may not have been revolutionary, but they were remunerative. Evans expanded his poster work into Hollywood proper. Among his more lasting efforts were John Carpenter’s Dark Star and Neil Young’s classic concert film Rust Never Sleeps, for which Evans did the posters, titles, and animated opening sequence.

“He liked to get really stoned and talk a lot,” says Evans of Young. “He had a lot of pop culture reference points. He was very specific.”

Evans also marked this period with an increasing fine art output, teaming up with photographer Robert Knight to do prints of rock legends such as Stevie Ray Vaughn, Jimi Hendrix, Slash and more. Evans painted on layers of colors, added texture, patterns, symbols, and distressed back- grounds to give the images an additional visual vocabulary that built upon Warhol’s pop vernacular.

He called the work “icon narratives” and his limited-edition prints of Sinatra, Monroe, Madonna, Elvis, and others found their way into some of the more high-end galleries of the day.

When the 1993 Malibu fire swept through Las Virgenes Canyon, the wood-framed California craftsman that used to be where Evans’ stone and steel house now sits, “blew up as easily as it burned down.”

“I didn’t know how scary a fire looked or how fast it moved,” Evans recalls. “There’s a moment when everything goes silent and you know that everything you’re going to have left is what’s in your car.”

When he returned after the fire, “the place was pretty much like the inside of a volcano.” At one point, a horse walked into his driveway, bewildered and unclaimed. “It was surreal,” says Evans.

Evans lost a great deal of his handcrafted archive. Even for a guy who has said he doesn’t mind throwing everything in the fire and starting over, this was devastating. “I had PTSD for awhile,” he says. “I couldn’t even look at fires.”

A pre-fire encounter with members of L7 and Nirvana at a party turned out to play a big part in Evans’ salvation. The bands asked him to do the first Rock For Choice concert poster, which he agreed to do. “And I liked it,” he says.

***

THAT POSTER INTRODUCED HIM to a whole new generation of creative people who had grown up decoding the work of Evans and Griffin and their peers. At the same time, the energy coming from the early ’90s indie music and DIY art scenes reminded him of the late ’60s again.

“It was a really creative time and having been there before, I knew how it was going to play out,” Evans says as we sit in his upstairs office, a sprawl of period-piece posters spread out on the carpeted floor. “It was almost like watching a movie of myself.”

Under the moniker TAZ (Temporary Autonomous Zone, named after Hakim Bey’s anarchist handbook) and in collaboration with his son, Gibran, and the master silkscreen artist, Rolo Castillo, Evans cranked out more than 200 concert posters for the likes of The Smashing Pumpkins, Pearl Jam, Beastie Boys, Jane’s Addiction, and for iconic events such as Lollapalooza and the Tibetan Freedom Concerts.

“That was my therapy at the time. I felt fine because I could do anything I wanted. I’d do a 50-foot screaming Buddha and they didn’t even question it,” says Evans. “It brought me almost full circle to where I started.”

But for Evans, back is only another way to the future. “He’s kind of a future outrider, really ahead of the curve, and not terribly interested in being a part of it when it hits the mainstream,” says Evans admirer and contemporary, Craig Stecyk.

Which brings us to the NASA-like configuration in Evans’ office. Encouraged, no doubt, by a lifetime of painstaking, hand-rendered work going up in flames, Evans became an early adapter of digital technology after the first Macs hit the mass market. “I couldn’t see technology turning back from there,” he says.

Evans moved into website development and viral marketing in the mid-’90s. He was undeterred by the millennial dot-com bust. “It was suddenly like they all thought dot-com wasn’t going to happen. I thought that would be like thinking cars weren’t going to happen in 1929.”

Soon, Evans was developing websites for films such as Men in Black, Seven, The Big Lebowski, and Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. As creative director of Atomic Pop, one of the first exclusively online record labels, it was his job to figure out how to digitally infect people with the personas of Public Enemy, Ice-T, The Black Eyed Peas, and others.

“An MP3 suddenly makes a song not very sexy. You didn’t have double-fold album covers anymore,” says Evans. “I became known for doing viral campaigns.”

Evans current creative incarnation, Division 13 Design Group, does this on a massive scale. Working for just about every major studio, Division 13 has done the websites for The Ring, Shrek, Saw, and Ice Age franchises, and dozens more films from Kung Fu Panda to Dreamgirls.

These days, though, a movie website isn’t just an online poster, it’s a portal to the parallel world that the film signifies. Making those worlds engaging is something Evans calls the “simplicity of attacking the psyche.”

Evans is content to attack the psyche from his command center in his concrete-and-steel bulwark tucked away in the Malibu Hills. Yes, he’s working on a series of fine art works that will apply many of the digital techniques to his iconic, hand-rendered images from the past, creating a whole new visual tableau of shape, color, and reference. But until that’s ready, he’s in the matrix.

“I find myself having interactions and collaborations with people on a huge scale and I never meet them. I’m okay with that, so I’m probably a good guy for the future,” he says. “The real experiences are going down to Malibu and surfing with my buddies and hanging out and going to movies. Then, to come back here and have the world as your playground is actually fascinating…the computer is the collective unconscious that Jung actually talked about.”