Goldsteinland

The Iconic James Goldstein and the Lautner Legacy

The man at his man cave. Photos by Steve Shaw, Treats Magazine

IN A GLASS-FRAMED photo on a glass desk in a glass and concrete house high on a hill, is pictured a fit young man with shoulder-length, shaggy hair. The man is resplendently dressed in a white, high-collared long-sleeve shirt, crisp, white slacks and black dress boots—a dandy in waiting, it would seem. The man in the photograph is years—maybe decades—away from his unlikely notoriety, but he already looks famous, like the DNA of a young Paul Simon and Doors-era Val Kilmer somehow collided. In his hand is a leash attached to an equally turned out Afghan hound. The dog is important, once the love of his life, the man has said. And it was for that dog that this whole thing started.

Another photo catches the eye. The man is naked and bears a resemblance to a young, sun-bronzed Iggy Pop had Iggy decided he didn’t like to sweat. In the picture he is flanked by two topless young women straight out of a California dream of sunshine and free love. Their knees meet above his groin and they smile like the fetching muses they once no doubt were. He stares hungrily at the camera, as if this was serious business. Maybe it was. There have always been fumes of rumors of flings with starlets and dalliances with lonely aristocratic women and mysterious heiresses but Goldstein will only let the pictures do the talking. “That’s me and Jayne Mansfield at the opening of the Whisky A-Go-Go in 1964,” he says casually. (One such rumor has Mansfield’s husband at the time sending a few goons to break young Jimmy’s legs.) You see, even though James Goldstein is a self-proclaimed “man-about-the-world,” traveling over 300 days of the year—to fashion shows, basketball games, exotic hotels in equally exotic lands—and has hosted some of the more legendary Hollywood parties at his house, no one really knows much about the man. And, it seems, he’s found the perfect persona: to be everywhere and nowhere at the same time.

There are plenty more photos on display like trophies. Here he is with Spike Lee, Penelope Cruz, Sean Combs, Snoop Dogg, Rihanna, Gisele, Cindy Crawford, Jean Paul Gaultier, Kate Moss, John Galliano…. In these, he doesn’t look like he did in the earlier photos. Eyebrow-raising haute couture, often crafted

from exotic animal skins, has replaced the understated class on display in the photo with the dog. The hunger in the photo with the nubiles is gone, too. Now, he is ripened by sun and age and by being able to have what he wants. The photos are no longer documents of becoming, but evidence of having become.

***

I MEET THE MAN in the photos, James Goldstein, on a brilliant, sun-kissed spring morning at his home on a hillside in Benedict Canyon, Beverly Hills. I would come up again weeks later and the sky was equally crystalline, the air breezy, the view pristine. One wonders if the weather is always perfect up here?

Goldstein greets me in a cap, running gear and running shoes, all featuring fluorescent, lime-green highlights. He is small and wiry with a deep tan and long, wispy white hair spilling down from his python-skin cowboy hat; he moves with the air of an alligator in the sun and his words are so carefully chosen that you wonder if they are being meticulously carved, like stone and concrete, in his mind first. His voice is a low, guttural baritone that never loses its monotone rhythm. The house where we meet, his house, is one of modernist John Lautner’s remarkable mid-century Los Angeles residences. It, along with The Chemosphere in Hollywood, Silvertop/Reiner Residence in Silver Lake, The Elrod Residence in Palm Springs, the Garcia House on Mulholland, have become symbolic of a certain sort of Los Angeles dream; be it design or lifestyle or both, which is, of course, as Lautner intended. And the Silver Screen has come a calling to shoot in these modernistic, almost cave-like structures—namely as dwellings of villains.

Goldstein’s house, known as The Sheats/Golstein residence, has been featured in The Big Lebowski and Charlie’s Angels: Full Throttle, among many others. Angelina Jolie got semi naked here for Timothy Hutton in Playing God. It has been speculated that Lautner’s stunningly bold creations attract Hollywood villains because they form perfect repositories for projecting limbic system overreach—flying too close to the sun, as it were. Or, to put it another way, since Hollywood traffics in mostly a puritanical moralism, despite its reputation, anything this good has to be bad. Goldstein, though, is no villain, especially when it comes to stewardship of Lautner’s legacy. He resurrected this remarkable house and, to some degree, Lautner himself. Thanks to Goldstein’s loving attention, this house is now part of the permanent record of aspirational LA architecture.

That Goldstein and Lautner would find each other could seem fated if you believed in that kind of stuff. Both grew up idiosyncratic independents in the conservative Midwest and both fell under the spell of Frank Lloyd Wright. Goldstein, the son of a Racine, Wisconsin department store owner, discovered his passions at an early age. A friend who lived a block away lived in a Frank Lloyd Wright. His father’s store was near the Johnson Wax plant, also designed by Wright. Thus began his appreciation of finer architecture, the modernist Wright buildings standing out from the typically drab constructions in Milwaukee and Chicago.

“Growing up, I was definitely focused on modern design,” says Goldstein. “I was always looking at new buildings.”

We’re sitting on the pool’s concrete deck, the sun is strong, the sky clear and the deck angles out above the horizon towards Century City, where Goldstein made some of his considerable, though somewhat mysterious, fortune. “Real estate investments” is all he’ll say on the subject.

Those early impressions lasted as Goldstein made his way out West as a young adult. “As I moved out here and started traveling to Europe and being exposed to more and more varieties of architecture, I developed an appreciation for old designs that I never had as a boy, but at the same time I wanted to have something thrusting into the future, rather than something from the past.”

I ask Goldstein if there was something in the optimism of Southern California’s embrace of mid-century American modernism that made him want to break from the past, and, especially the Gothic Midwest where a thirteen-year-old Jewish boy who liked to dress in pink suits might seek reinvention in the wide open West. Goldstein reflexively dismisses the psychobabble, but hints around its margins anyway.

“Nah, I don’t think that was the case,” he says. “I like the clean, minimal look together with the feeling of the future and something that had never been done before,” he says. “I liked the idea of creating something new and I liked the feel of openness, of bringing the outside to the inside. All of those things.”

***

HELEN AND PAUL SHEATS commissioned The Sheats/Goldstein House, as it’s known in architectural circles, in 1961. The couple had worked with John Lautner before in 1948 and 1949 on the L’Horizon Apartments in Westwood. The L’Horizon Apartments, with its space-age curves and dramatic angles, can be seen as a modest banner raising for Lautner who strives to set himself apart from the more formalist Frank Lloyd Wright protégés who preceded him here—Rudolph Schindler and Richard Neutra. Those two, perhaps more celebrated modernists, stayed mostly true to the egalitarian/socialist ontology of modernism (an aesthetic that would take decades to become the stuff of bourgeois desire), while Lautner was a little bit rock ‘n’ roll—a maverick even within the progressive Frank Lloyd Wright school.

Lautner was born in 1911 in Marquette, Michigan, to an academic father and artist mother. Lautner’s parents were art and architecture enthusiasts and key influences on Lautner. The Lautner family built their summer home on Lake Superior themselves. Lautner’s mother designed and painted all the interior details—a formative experience for Lautner who in later years would pay as much attention to the interiors of his homes as the exteriors. Lautner studied philosophy, ethics, literature, drafting and architecture along the way to earning a bachelors degree in liberal arts at Northern Michigan University, where his father taught.

Though his parents were both fans of architecture and building, Lautner had little interest in the formal aspects of drafting and preferred, even during his fellowship at Frank Lloyd Wrights Taliesin studios in Wisconsin and Arizona, to stay out of the drafting room and get his hands dirty in the construction process, something he learned to love building that summer home.

Lautner came to Los Angeles, like Schindler and Neutra before him, to supervise various Frank Lloyd Wright commissions. He built his first solo project, the Lautner House, on Micheltorena in Silver Lake, in 1939, a year after his arrival. It was an auspicious beginning, featured in a big splashy spread in Home Beautiful magazine and was praised as the best house in the United States by an architect under 30 by the eminent architectural historian Henry-Russell Hitchcock.

It didn’t take long for Lautner to showcase his derring-do. In the mid-to-late 40s the iconic coffeehouse aesthetic known as Googie architecture was born, taking its name from the Lautner-designed Googie’s Coffee Shop on Sunset and Crescent Heights, which followed the three Coffee Dan’s restaurants he designed. The style—with its signature cantilevered structures, boomerang shapes, upward tiling rooftops, acute angles and high-energy scripts—became synonymous with the atomic-age kitsch that was often derided as too lowbrow and vernacular to be taken seriously by the architectural establishment. More recently, though, a critical reassessment has recognized Googie’s value as an expression of sunny postwar populism and a worthwhile emblem of the times. No doubt, nostalgia has played a big part in that reassessment. But, the playfulness of the style, the optimism and the eye-catching forms would all become integral elements of Lautner’s palette.

While Googie made a lasting impression on the commercial landscape of Southern California during its postwar coming of age, Lautner set about in earnest putting his stamp on the area’s residential aesthetic in the mid-50s, beginning with Silvertop in 1956. Then the Chemosphere followed in 1960, the Sheats (Goldstein) Residence in 1960 and the Elrod House in Palm Springs in 1968.

Lautner integrated the boldness of Googie design with the unique challenges each home presented. The Chemosphere was an answer to the “insane” (as he called it) practice of digging into steep hillsides to build foundations and structures. The Elrod House perfectly fits into the rugged desert bluff on which it is built. Silvertop looks as natural on the hilltop overlooking Silver Lake Reservoir as a cherry looks on top of a sundae. Surrounded by gauche neo-classical mansions rising up like warts in the foliage above Beverly Hills, the Sheats/Goldstein House is as unobtrusive as a cave in the side of a mountain. That Lautner manages this integration with the flair and style that set him apart from his contemporaries is testament to his particular genius.

photos by Steve Shaw, Treats Magazine

***

GOLDSTEIN ALIGHTED from Milwaukee at 18 to go to Stanford. There he studied math and physics, but decided he wanted to get into finance and came to Los Angeles for grad school. Another problem with staying in the Bay Area: It had no professional basketball team at the time. Though he was yet to become, in the words of NBA commissioner David Stern, “the single biggest and most extravagantly dressed NBA fan in the world,” basketball was still a passion, going back to his teenage days as a statistician for the Milwaukee Hawks.

“At that time,” Goldstein says of his arrival in Los Angeles, “I was still involved with football and baseball, as a spectator, but I realized as the years went on that those sports didn’t provide the same excitement for me as basketball. So, I decided I would specialize in basketball and dropped out of these sports and now basketball is almost a year-round occupation for me. Even in the summertime, I go to summer league basketball and I go to international league basketball. It got to the point where something I never anticipated happened and I became very famous as a result of my basketball involvement. And now I know almost everyone involved in the game—owners, players, management, ball boys.”

I caught Goldstein on a rare day off from this hobby. Sitting near the opalescent pool, with shadows dancing on the water, he tells me he’s been to 19 games in the past 19 days and the reason he is sitting here with me now is simply because there are no playoff games on this day. If Goldstein isn’t jetting off to a playoff game, he might be heading to fashion week in Paris, Moscow, or Milan sitting, of course, in the front row at the catwalks as his leggy model “friends” gallop the runway in front of him. He speaks proudly of his “enormous” hat collection, many made from rare reptile skins—cobra, python, anaconda—purchased from a mysterious hat maker on a small, serpentine street somewhere in Paris. “I buy all my hats from him now,” Goldstein says, like the gentlemen is in the CIA protection program. “He’s a great hat maker and I only wear his hats these days which means I have a lot of other great hats that I bought years ago that never leave the closet.”

He learned to love clothes from his father, but says at a young age he began moving beyond his father’s conservative dress to his own creative style. When pink became a fashionable color in his teen years, he went all the way and dressed in all pink suits. In his early 20s, Goldstein made a trip to Paris and was bitten by a lifelong fashion bug. Goldstein’s business card says: FASHION, ARCHITECTURE and BASKETBALL on it, and it might be hard to determine which of those pursuits he’s spent more time and money on.

Goldstein’s early years were spent living in various apartments in West Los Angeles. But, then came Natasha, the Afghan hound and love of his life. The dog needed room to roam. So Goldstein went house shopping.

***

THE SHEATS’ RESIDENCE had gone through several owners before Goldstein came upon it. In each case, the owners had insufficient funds to realize Lautner’s design. Substandard materials—plaster, formica—were employed to fill in the gaps. Goldstein found wall-to-wall green shag carpet throughout the house, the poured-concrete structures, including the triangle-patterned living room ceiling, was painted in black, white and green, the bedroom done in turquoise. It was like the 70s gone wild.

“It was a mess,” says Goldstein, “but I could see the brilliance of the design.”

The house, as with all of Lautner’s residences, was designed to accommodate, not compete with, its environment. Built into a sandstone ledge high up in Benedict Canyon, the main structure spreads out at a 45-degree angle from the eastern rise. The entrance on the northern end, set against a dramatic jungle-like hillside, opens into a den, kitchen, dining area and a living room with cement banquets for seating and a beautiful cement, wood-burning fireplace where the northwest angles meet. The living room opens to a pool surrounded by a cantilevered, pebble-concrete deck that juts out into the horizon towards the Santa Monica Bay. It has to be one of the greatest man-caves ever conceived.

James Goldstein bought the Sheats House in 1972, 10 years into its existence, for $182,000. “I know, it sounds kind of shocking,” he admits.

Prior to buying the house, Goldstein spoke with Lautner on the phone.

“He expressed his pride in the house and strongly recommended that I buy it, but he hadn’t been over to see what had been done to it until roughly 1979 when I brought him over—his mouth fell open.”

Lautner had originally conceived of the living room being open to the pool area with an air curtain protecting the “inside.” In other words, no obstructions, not even glass, to the outdoor environment. That never came to pass. Instead, previous owners had put in glass windows intersected by horizontal and vertical steel mullions. It was the exact opposite of intent. Goldstein’s first project with Lautner was to remove the mullions and replace them with frameless glass. Lautner was all for it.

“That was the first construction project I’d ever been involved with in my life and the first thing I had done to this house,” Goldstein remembers. “Once I got my feet wet with that project, I was off and running with more things that I wanted to have done.”

Goldstein and Lautner spent 15 years together trying to “perfect” the house. “We hit it off and I could see that we liked the same things and we both had a rebellious streak and didn’t like conformity or the corporate mentality,” says Goldstein.

I ask if it was the beginning of a happy ménage-a-trois, between he, Lautner and the house.

“It wasn’t just the love of the house, it was the way our minds worked,” Goldstein replies, ignoring the quip. “He was always very receptive to my ideas and what I wanted to do to improve the house. At the same time, he never imposed anything, or told me ‘This is what I’d like to have done,’ sometimes to the point of frustration because I would have liked to have heard his ideas.”

Goldstein pauses. He looks around for a bit and continues.

“He always waited for my ideas and took them and enhanced them. He would typically come up with several alternative sketches for any of my ideas and allow me to pick the ones I liked the most and then we would do a small model of it and then we would do some actual mock ups and then we would start the construction of it. At each phase of that development, we’d be making modifications as we went along, including the final construction phase.”

He pauses again as if he is replaying the action in his head.

“There would always be modifications to try to make everything as perfect as possible without any regards to what it would cost. There was never a budget; there was never an estimate. It was always, how can we make this as perfect as possible without any regard to the cost.”

Talk about a dream client. Architecture is a tough racket and even Frank Lloyd Wright was constantly struggling with money. Goldstein, with his sweeping program of first setting right, and then advancing the designs, must have felt like a godsend to Lautner in his sunset years.

I ask Goldstein, who estimates he’s put $10 million into the project so far, if he had a big picture in mind or if the property evolved incrementally.

Long pause.

“I have to say, I didn’t see a big picture,” he says. “Maybe at some point later on I did, but I started out working incrementally and eventually I replaced the glass in the house with frameless glass, for example. Then, I just worked on every room of the house to try to achieve perfection. When I pretty much completed the revisions to the house, I still continued to work on little details.”

***

GOLDSTEIN TAKES ME on a tour. One that he’s must have done hundreds of times—from Lauternites to movie stars to international architecture buffs to drunk party guests looking for an adventure. He moves slowly, making sure no anecdote is left out, and no matter what magical or beautiful thing he points out he never breaks from his non-plussed demeanor. The attention to detail is astounding. There is so much to take in, it’s almost overwhelming. He points out the skylights on the roof overhanging the pool deck, which were filled in with drinking glasses by previous owners to save money.

“That turned out to be a great idea,” he says.

The original pool had a waterline beneath the coping, surrounded by Mexican tile. Goldstein replaced the tile with concrete, per the original design, and raised the water level to affect an infinity pool. He added a planter on the west side.

The pebble concrete in the living area which was covered with green, shag carpet, Goldstein tore up and replaced the concrete bit by bit. The fireplace was made of rocks and Goldstein replaced it with concrete to match the buildings poured-in-concrete structures.

Goldstein put in a two-level koi pond with a waterfall and concrete steppingstones. The Lautner designed banquets are about the only thing that stayed as is inside. Retractable skylights were added. Goldstein fingers some controls and in a minute the sky is just a ladder as we stand in the kitchen. Other details: the main table-bookcase running along the eastside of the house is a beautiful concrete and wood piece, done by Lautner and Goldstein, that used to be Formica and plaster cabinetry. A glass and concrete dining table that seats eight was designed and installed, a kitchen bar added. It’s safe to say, given Lautner’s affinity for interiors and the minimal opportunities to get his hands on them, the two enjoyed themselves.

As we move around the house, Goldstein straightens out picture frames, wipes counter tops clean. Everything is so precise and immaculately maintained one might hazard to think it’s to the point of near compulsion. Dozens of book cases are stuffed with books on travel, fashion, architecture and basketball. Magazines, from all eras, form perfect skyscrapers that dot each room.

A fun feature of the house is that you have to exit the primary living space to get to the guest bedrooms and the master suite. This forces you outside along the moat-like concrete decks and into the incredible environment Goldstein has submerged his house into. Indeed, the ambient sound of running water from the waterfall reinforces the feeling that somehow you’re inside a sort of submarine surrounded by a sea of green. That, too, is by design—Goldstein’s.

The only time Lautner and Goldstein had a difference of opinion happened to be over the landscaping. Goldstein fell in love with tropical places when he “escaped” Wisconsin and wanted to move in that direction. Lautner preferred to plant pine trees. “He didn’t oppose me, but I could see he didn’t understand it either,” says Goldstein.

I would have to say Goldstein got it right. He bought up the surrounding acres ascending down the hill to the street below and began planting tropical plants. “And that was the start of an immense landscaping project that has been continuing on for 20 years,” he continues, as we descend concrete steps to his bedroom. “The hillside is apparently perfectly situated because the sun moves directly onto it,” he tells me. “My landscape architect, who specializes in tropical vegetation, is amazed himself at the way some things thrive here.”

We take a detour along one of the stone pathways and come to a deck jutting out into the thick forest. It has a glass bottom and peering down into it gives one the sense of looking into a kelp garden through a glass-bottom boat. As weird as it sounds, given that we’re high up in the hills, the entire environment has the feel of looking into an aquarium or being submerged in an underwater observatory.

“It didn’t start out as an ecosystem, but I think it ended up that way,” says Goldstein.

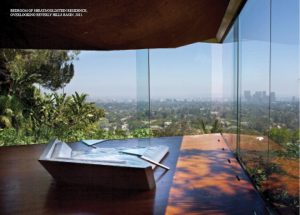

We go down to the master bedroom. It features a pie-shaped leather couch with two raised, pie-shaped glass end tables on either side. The couch points out towards the northwest, an ideal spot from which to watch the sunset or the fog roll in. Windows above the bed offer a view into the pool.

Goldstein stops to adjust some books and pictures that only he would notice were out of place and apologizes for the mess, explaining that he’s been away for a while. He opens the closet next to the bed and pushes some buttons and racks of clothes start marching past us on a rotating wardrobe.

“Here’s the closet that probably houses one of the great men’s collections in the world because I buy very special pieces,” he says. Anyone who has tuned into a Lakers game and wondered who is the silver-haired gent in the green and purple and red snakeskin suits would have to agree.

Goldstein tells me his favorite designers are John Galliano and Roberto Cavalli. “Every season, I buy a new collection of clothes and this most recent season my favorite pieces are from Balmain. I’ve found that men’s clothes are very boring at the moment. Balmain makes some amazing jackets for women that have no real sexual connotation of any kind because they are motorcycle jackets. I’ve bought a couple of them.”

While his clothes collection is flamboyant and flashy, and a Lautner house is almost flashy by definition because of the bold designs, Goldstein’s taste when it comes to the property is pretty refined. Even the large sculptures on the grounds, one of wood, the other concrete, are masterfully integrated into the space. I ask him about the dichotomy.

“One is meant to last forever, the other is meant to last six months,” he quips.

We descend further into the man made jungle, Goldstein bounding about like a mountain goat, me panting to keep up. Everywhere there are diversions—pathways leading to vistas of either the inner space he’s created or the outer space that surrounds it—the city, the basin, the sky, the sea, appearing for seconds, then vanishing as you snake through more canopy’s.

Then, as if from a Disney movie, the trees part and give way to an open area in which is nestled the Goldstein Skyspace, also known as “Above Horizon.” The structure was intended to be an arranged marriage between renowned light and space artist James Turrell and Lautner.

“I saw James Turrell’s work in museums and also at the Pace Gallery [in New York] and I was really excited about it,” explains Goldstein. “I was thinking, and this probably goes back to 1990, that I wanted a collaboration between Lautner and Turrell, the three of us had a couple of meetings and things were underway but getting the city to approve this was a laborious process. It took a number of years and by the time I was ready to start construction, Lautner was no longer around. So, then it became a project with me and Duncan Nicholson [Lautner protégé and Goldstein’s architect since Lautner’s death in 1994] and Turrell.”

Turrell provided the specs and dimensions for the room and Goldstein and Nicholson did the rest. It’s an astonishing, almost Gehry-ish structure, jutting out from the green forest into the eternal blue sky. Goldstein had the idea to add a window in the southeast corner, “which Turrell went for and it turned out to be a great addition.” The effect is something like looking through porthole and catching a glimpse of the great sea outside.

Goldstein fumbles with a remote control that looks like something that would operate a Wii console, and a section of roof peels back to reveal the blue sky.

“That show starts at 7:30 tonight,” he says. “It’s not a sunset you see, but you see the changing colors of the sky. The sky doesn’t look like the sky. It looks like the ceiling of the room.”

I ask if he ever meditates here.

“I’m not sure what that means,” he replies dryly. “I enjoy the experience no matter how many times I’m here. I’m not sure if you call that meditation.”

***

GOLDSTEIN FINISHES THE Skyspace six years ago and turned his attention to his current major project, a multi-use facility on an adjacent property that will sit beneath a tennis court. The space will host a theater complex, nightclub, a large bar, massive DJ booth, a guesthouse, kitchen and surrounding deck/dining area. The structure will be bigger than his primary living space.

“I like the idea of separating my house with all the personal possessions from where the parties will be,” he says.

I ask Goldstein, given his obvious flair for style, if he ever thought of getting into fashion or design as more than a hobby.

“People say that all the time—you should be an architect or you should have your own clothing line, but, number one, my tastes are too extreme to be popular from a commercial standpoint and number two, I don’t want to get burdened with the business at this point.”

It’s a little cliché to say, but it feels a bit like an Eden up here, although, perhaps, an isolated one. But it’s certainly splendid isolation if it is that. I ask Goldstein how he ever leaves. “I love traveling, so now I’m only here five or six months a year.” I suggest he could rent the forthcoming guesthouse to me for $800 a month. He laughs.

Goldstein tells me he’s dropped out of the LA social scene recently and doesn’t entertain as much as he used to, something he hopes to take up again when the new facility is complete. He doesn’t know exactly when it will all be done, but guesses it could be up to five years. “They’re supposed to pour the concrete on the tennis court this summer,” he says, a bit skeptically. When I suggest he may kick the bucket before this is all complete, he chuckles and says, “Yeah, but what can you do about that?”

I can’t help but wonder if Goldstein ever wanted someone to share this all with. He’s never been married and that he says he never really wanted to be.

“I need to be free,” he says. “I don’t like the concept of marriage—the legal aspect of it. I want to be with girls I have a good time with and react on the spur of the moment without feeling I have to be with someone. I’m also very independent and I operate on my own quite well. I don’t need to have someone with me all the time.”

Case in point: his entire staff goes home at night. When Goldstein is in town, he’s usually out by the pool, or if the weather doesn’t permit, in the den watching TV, basketball most likely.

As it turns out there is someone Goldstein wants to share this all with. When he does pass on, he plans on turning the entire estate over to an institution, “so it can be maintained in the future in this form and be an inspiration, hopefully to people who appreciate good architecture.”

Somewhere, John Lautner is smiling in his grave.